Taking American Jazz to Japan and Back with Tommy Campbell

If there is one thing I learned from this conversation with Tommy Campbell, it’s that nothing can prepare you for a conversation with Tommy Campbell. Just like a magnificent jazz improvisation suddenly resonates with the feelings that you didn’t even know existed, talking to Mr. Campbell makes you feel like you went on a trip to a far away planet. He’s not your guide there; he is the planet. With a personality of that scale, he certainly doesn’t fit in the narrow frame of an interview, but even a glimpse of Planet Campbell can make anyone a happier human being.

Katia Mukminova

I was looking at some videos of your performances and suddenly spotted a green alligator squeaky toy in your cymbals. What’s the story behind such an unorthodox band mate?

Tommy Campbell

It all started in Japan when I was buying toys for my son who was about 2 years old at the time. I started going to “a 100 yen” stores in Japan. First, I found a cashier’s bell and I got sidetracked by that because it was a bell! And I thought, maybe I’m gonna put that on the floor and just occasionally, at the right time when there’s silence, I could ring that bell. In Japan it’s a tradition, those sounds of high bells, low bells, you know. So I did it, and it worked. And then I bought squeaky toys for my son, they were frogs, very colorful. In Japan, they love fish, they appreciate the beauty of the sea. I eventually started putting those rubber animals on my drum sets, not too many, maybe one or two. And then it grew. They were more pretty than useful but some did make interesting noises. I had a bicycle horn in B-flat!

After 3/11 in Japan, the tsunami which I was in, I was coming back to New York and I was definitely trying not to bring unnecessary things back with me because of the shipping costs. So obviously, if I brought those things, those duckies and frogs, they’d have my head on the platter! So I made sure I was empty when I was on my way to the airport. When I got to the airport, one of my fans was there and she had a going away present for me. And it happened to be a pig, man! Of course, I took it but I knew I wasn’t gonna use it — I just got rid of all my animals.

Anyway, I got back to New York, I started playing with different bands and eventually put together my own band… After everybody got used to me and I got used to the music and met the people, I pulled out the pig. Now, every gig that I show up to where the musicians know me, somebody will ask me, “Did you bring the animals?”

KM

KM

Were you ever shamed by animal rights activists? Because those toys look like they’re suffering when you squash them with those cymbals!

TC

No, but the only time I was nervous is when I went to Turkey and was dragging the toys through security. I was wondering what people were going to think but there was no problem.

I get a lot of jokes about the toys. Like, this bass player named the pig “the porkestra!”

KM

You grew up in Philadelphia and then you moved to Boston and New York. What are the differences between the schools of jazz in Philly and New York?

TC

First of all, to clarify, people know I’m from Philly but I’m actually from a town called Norristown, Pennsylvania, which is about 25 minutes outside of Philly. My uncle Jimmy Smith was also born in Norristown, and Jaco Pastorius was also from Norristown.

It was so nice growing up in the suburbs! We had beautiful lakes, streams, mountains, hills, we rode our bikes and snowboards, we did ice skating. I had 42 trees in my yard alone. Yeah, man, I’m telling you, I was really so lucky to grow up there! I went to a predominantly white school but very mixed, there were a lot of different cultures. We were too young to know at the time, but it turned out to be a blessing.

So to answer your question, I really don’t know the Philly scene so well. I played a lot of rock when I lived there. I knew that my uncle was Jimmy Smith, but to me he was known as Uncle Jimmy. I didn’t really know he was the Jimmy Smith until I was 17, my first year at the Berklee College of Music. It’s weird. It was a while until I met a few people, like Kevin Eubanks who was born in Philadelphia. I met him way back then as well as his brother Robin Eubanks.

Growing as a drummer and being a little better at it — you’ve gotta go where it’s happening, you know. Or where it’s happening will find you! I did know just a little bit about Philly before going to college at Berklee. I found out about the Philly scene when I got back there and played there with Sonny Rollins and Dizzy Gillespie.

KM

How did living in Boston influence you as a jazz musician?

TC

In Boston, I learned a lot about ECM music: Keith Jarret, Paul Motian, Bob Moses, Pat Metheny and so forth. That was really good for me, I would never be able to figure it out on my own. I first met Terri Lyne Carrington when I got there, she was 12, I was 17. Her father used to pick me up every Saturday and take me to their house. He wanted her to learn how to play funk, and I was a funk drummer. I had no jazz jobs, and Terri was studying with Alan Dawson! And she was already miles ahead of me! So she gave me jazz lessons and I gave her funk lessons. That was great!

KM

You once said that “half of playing is listening.” Is this your recipe for successful collaborations?

TC

I love conversation in music. Between two instruments, or people. Sonny Rollins taught me this one about listening, oh my gosh… Oh! He really gave it to me. When you are talking and people are listening to you and you know that you have their undivided attention — and you might not even know what you’re saying, you might be just trying to work something out in your head — but they are listening, waiting for your every thought… It’s the same with music. Oh, it makes a musician feel so good when you know the other person is listening and ready to respond! And if they really reacted, you do something with what they said; you let them know you understood what they said and you take it to the next level. It’s really rewarding. This is one of my goals in being a musician and playing artistically.

KM

Speaking of audiences — Japan, where you spent so many years, boasts the largest number of jazz lovers in the world. What’s your expert opinion, why do they love jazz so much?

TC

Because it’s so different. Jazz — it comes from blues basically, right? But in Japan, they had no blues, there’s no blues anywhere, not even close, nothing! Except, their blues is enka music. It’s a dance kind of music. It’s their blues — it doesn’t sound like it but it is. It has so much feeling and a deep groove. But their groove is not on 2 and 4, like we have it in jazz, their groove is on 1 and 3. It’s a weird feeling — you can’t relate it to jazz, but the groove is deep, really deep. It was explained to me by a few respectable musicians, like Sadao Watanabe and Chin Suzuki. They sat me down and let me experience the other side of the beat.

So, the most popular blues in Japan, and I mean across the board, not in small circles, is Route 66. That’s kind of where they start, something major. They’re almost obsessed with importations. A lot of classic and jazz musicians have traveled there.

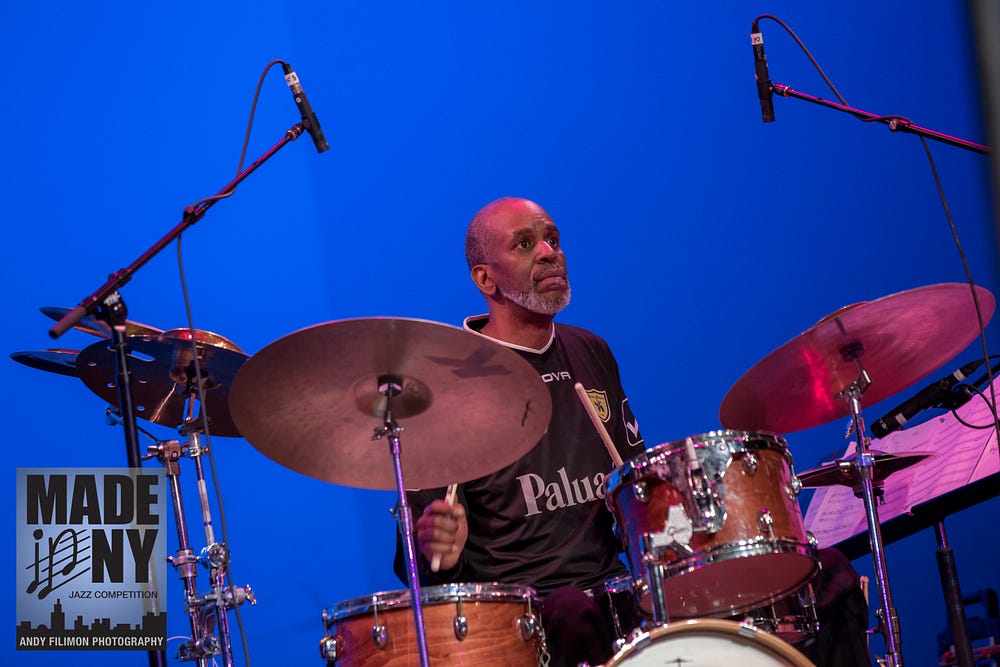

Tommy Campbell, Madeinnyjazz Gala, NYC 2016, picture by Andy Filimon

KM

They’ve done some amazing experimental stuff, like Minoru Muraoka’s jazz fusion and classic jazz standards with traditional Japanese instruments. What drives them to take such a foreign music genre and make it their own?

TC

Here is what I found out through my own experiences. When Japanese people — or any kind of people — when they see somebody who resembles them doing something interesting, they’re drawn to it because they can relate. When you’re Japanese and you see a hip-hopper or a brother from Pittsburgh, you can’t imagine yourself doing it because you don’t look anything like that person. So they change it, they alter it; everybody does it in their own way depending on which country they’re from. They make it feel like it’s the same thing that it was but they put their own little touch and feel on it. Sometimes they get it right, and it does have the right elements to make it what it should be; but sometimes they can’t find anything similar to keep the same elements, so you get variations of jazz. I played with a group in Japan that had all their instruments made of bamboo: the drums, the bass, the guitars — everything on the stage was made out of bamboo! But you need a few people in the band who can bring the groove element; if it’s just bamboo up there, it’s not gonna make it interesting jazz, you know.

So my point is that I’ve seen all levels of musicians in Japan, the best and the worst, just like we see it anywhere. But the more experimental they get, the less of the true element of jazz remains. There were a lot of interesting things, too… But not like in New York, man!

I miss Japan so much, man, I really do, but there are things here that Japan doesn’t have. And vice versa.

KM

You came back 5 years ago, and now, working with Made in New York Jazz Competition, what do you think are the greatest challenges for young jazz musicians in New York now?

TC

You have to make contact with people more. You have to get out and talk to people, touch people, feel people. You have to meet people online, listen to this, hear that. So that’s one thing.

A couple of days ago Randy Brecker reminded me what he had told me years ago. When he was a young man, if a new Miles Davis recording was to come out, there would be a line to the store around the block. Now, oh my gosh, there are hundreds of CDs released every week. It’s so much more now! So many directions!

KM

Is there more talent now or just more opportunities?

TC

I think there’s more talent. It’s not as much as people are led to believe by Instagram and Facebook, but there are some great talents who are taking it to the next level; there are some genius young people out there. But because everyone can be advertised so easily these days, it tends to look more than there actually is, in my opinion.

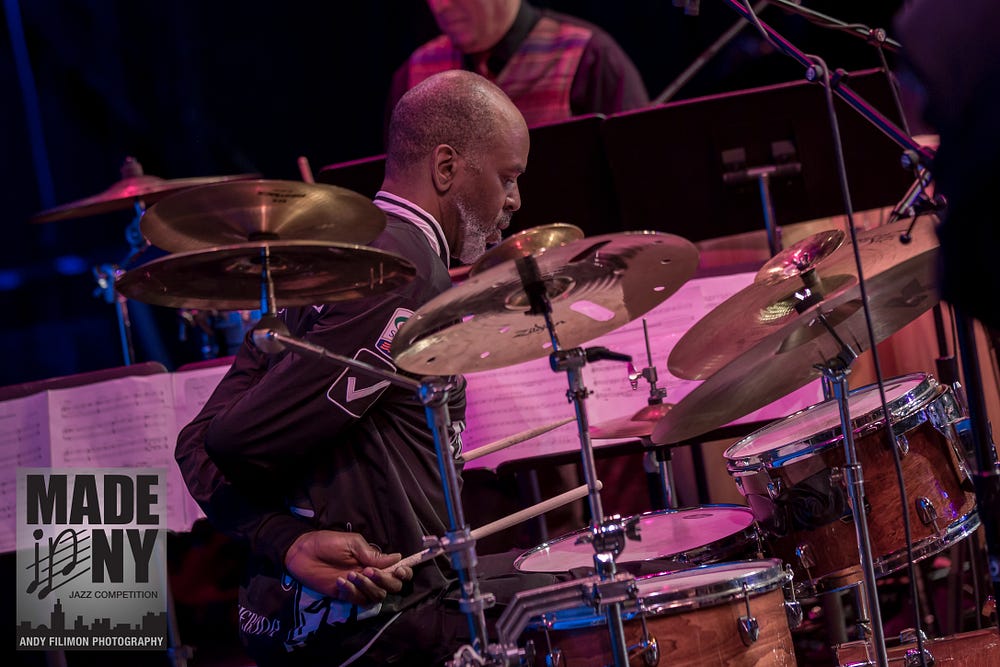

Bobby Sanabria, Julia Malaspina, Federico Malaman, Tommy Campbell, Misha Brovkine. Karim Maurice

KM

Having said that, how do you feel about the future of jazz? Are you optimistic?

TC

Jazz is here to stay and many more styles are here today and will be here tomorrow. Not all of them, but many. I’m just happy that jazz is famous all over the world, and that’s why I get to do my “job” — I hate that word, which is why I don’t have any money, probably. I hope I don’t get in trouble for saying this, I noticed one thing when I came back — maybe it’s ’cause I’m older, too, but I don’t think so — musicians here in New York use the word “work” at the wrong time, man! Which makes their product feel like they’re just working, you know. And when they’re done, they’re done. A very common expression that I hear a lot here in the realm of jazz industry is “Hey, man, where are you working tonight?” They said it back in the 40’s, too, but for some reason it wasn’t the same kind of work. I don’t know, I hate that phrase. But if you hate it, you might end up not working and with no money, so it’s tricky. People are selective about it. When I was young, it was less work — even though we were working, too!

Lately, I try to be on both sides: I keep my tuxedo, my black suits and whatnot at home, I can do any kind of gig (I hope). So when it’s time to work, I’m ready. But we all want the stuff that’s interesting, something that we enjoy and would want to do for free.

Katia Mukminova

Exclusive for Made In New York Jazz Competition

by Katia Mukminova, a freelancewriter and jazz lover. Currently lives in Brooklyn.